“Prossalendi’s Britannia” – Contemporary Perspective

Ionian Academy, Corfu, 1 – 29 September 2018 – Eventbrite

CORFU.- As it is well known, George IV, when he was Prince Regent of the United Kingdom, founded the Order of St Michael and St George in Corfu and in Malta on 28 April 1818, two hundred years ago. This forms part of Corfu’s history and belongs to its heritage. To celebrate the Order’s bicentenary, the Corfu Heritage Foundation is organising the Corfu Festival 2018, which is to include a series of cultural events encompassing literature, music, visual arts and sports.

This Festival is taking place under the auspices of the British Embassy, Athens, the Hellenic Republic’s Ministries of Culture and Tourism, and the Municipality of Corfu, between 7 July and 30 September 2018.

The “Prossalendi’s Britannia” is organised in two separate perspectives. The Historical Perspective, which was presented in the past, concerned the sculptural group that was designed by Paolo Prossalendi (1784-1837) and crowned the façade of the Palace of St Michael and St George in Corfu during the period 1823-1864. The Contemporary Perspective is supervised by Dr Megakles Rogakos and curated by four Research Associates – Mr Ioannis N. Arhontakis, Ms Georgia Damianou, Ms Georgia Kourkounaki and Dr Constantinos V. Proimos. The Curators have commissioned distinguished contemporary artists – Greek and foreign with respect to gender – to recreate their own version of Prossalendi’s Britannia through their personal visual idiom and vocabulary. So, the Contemporary Perspective features 32 works by an equivalent number of artists – Emmanouil Bitsakis, Lamprini Boviatsou, Thodoros Brouskomatis, Ricardo Cinalli, Dimosthenis Gallis, Milly Flamburiari, Nikos Giavropoulos, Ken Howard, Marion Inglessi, Yanna Kali, Stella Kapezanou, Aris Katsilakis, Alexandros Maganiotis, Georgia Matsamaki, Dimitris Merantzas, Alkistis Michaelidou, Nicholas Moore, Konstantinos Pardalis, K. N. Patsios, Aglaia Perraki, Artemis Potamianou, Natassa Poulantza, Irene Pouliassi, Vagelis Robolas, Margot Roulleau-Gallais, Dimitris Skourogiannis, Anna-Maria Smyrnaki, Aris Stoidis, Shubha Taparia, Yorgos Taxiarchopoulos, Olga Tobreluts and Amikam Toren.

Finally, Professors Harris Kondosphyris, School of Fine Arts of the University of Western Macedonia in Florina, and Panagiotis Kyratsis, Technological Educational Institute of Western Macedonia in Kozani, with their students will present a new sculpture, relating to Prossalendi’s Britannia, to be submitted to the Central Archaeological Council with the prospect of it being displayed either temporarily or permanently in the place of the missing sculpture on the Palace’s façade.

The Contemporary Perspective of the “Prossalendi’s Britannia” exhibition will be presented at the Ionian University, Corfu, in the period 1 – 29 September 2018. – Eventbrite

“Prossalendi’s Britannia” – Contemporary Perspective

The exhibition is supervised by Megakles Rogakos (MR) and curated by Ioannis N. Arhontakis (IK), Georgia Damianou (GD), Georgia Kourkounaki (GK) and Constantinos V. Proimos (CP).

[The dimensions are given in centimetres – height before width before depth]

Emmanouil Bitsakis (Greece, b. 1974). Good and Bad Government, 2018. Acrylic on canvas, 25 x 25.

The title of the work by Emmanouil Bitsakis refers as a political commentary to The Allegory of Good and Bad Government fresco of Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1290-1348) that is located in Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, but without the slightest pictorial reference to the famous work. Contrary to Lorenzetti, the artist organises his painting’s composition as a post-surrealist iconographic collage with Britannia appearing in profile, following the design of corresponding coins, middle-aged and tired, gesturing strangely, as a patriotic traffic controller, bound by in his daily task of achieving good government at home and overseas. The tunic on loan from Pallas Athena has been removed and Britannia appears in her lace underwear without any trace of provocation but only with reference to her delicate bourgeois origin and her present poverty. Scattered fragments of marble relief link the artist’s composition to the sculptural origins of Prossalendi and define the indirect reference of British art to its Roman origin. And in the background the sea, the landscape of the glorious domination of two centuries of the British Empire, which identifies the insularity of British soil and hints at the central political British pattern with a prow in the form of a crowned bird giving at the same time the ‘official’ measure of the old mighty glory, which was undoubtedly achieved due to Good Government, and which was fatally flawed due to Bad Government. IA

Lamprini Boviatsou (Greece, b. 1975). Can you live without your shield?, 2018. Graphite and coloured pencils οn wood and oil οn steel, 120 x 65 x 5.

Lamprini Boviatsou’s work, Can you live without your shield?, is a special self-portrait portraying the essence of Britannia and Pallas Athena with all the intimate thoughts of the painter being transported from the collective level to the ultimate personal experience. Britannia-Athena-Lamprini is standing opposite the viewer with bulging eyes, full of questions about everything that is happening around her, in a world that is changing, defending and redefining itself. She wears a classic Greek chiton whose rich folds partially conceal the façade of a neoclassical mansion with a dark gallery, at whose top the inscription BREXIT flashes temptingly. A frightened owl in the form of consciousness springs from within the ancient Greek helmet holding a burning message on a scroll. And all these things happen behind the metal shield, embellished with the personalised cartographic image of the British Isles. The artist’s successive allegories pose fundamental questions about the course of the British Empire from its world domination to the inward choice of leaving the European community. They confirm the rapid global change of the situation, sweeping away the private path, initiative, independence, even the existence of citizens, who as weak elements accept the collateral losses of the overwhelming changes. Weak to react to the storm of developments they turn into mere observers of the new situation with open eyes. What defensive mechanism, which shield could defend the personal and private rights of every citizen? How does one, as a citizen of a global commonwealth, become a citizen of an isolated island country? Each personal question has a separate answer, every separate glance of the viewer on the shield also gives a distinct refractive image of personal solution to the collective problem of private defence. At the edge of the shield, the small figure of Prossalendi is seen to be sceptical… IA

Thodoros Brouskomatis (Greece, b. 1963). sa(i)l(e)s, 2018. Digital print on photographic paper, 50 x 60.

The artistic language of Thodoros Brouskomatis, touching the boundaries of kitsch and pop art, creates a dreamy landscape that recalls the collages of Dadaists and works of surrealists. With the technique of photocollage, the artist presents a timeless cultural setting, paying tribute to the Ionian Sea, the place where for centuries the history of the East and the West meets. Cultural elements that represent different cultures and geographies are part of the waves of the sea that have been loved as much by Prossalendi as by the people found in it. The composition describes a utopia of bliss, emerging from the subconscious and the dream, citing the absurd. Works of art of past centuries have not only acquired life, but are given will and reason. The cultural capital of the place is found in the present time, having acquired the aspect of pop idols starring, as an attractive poster, with slogans to scatter a protest. The protagonists of the artist revolt and cause us to observe them outside their frame, isolated from the images of art history books and tourist guides. They claim their place as works of art, as creations that belong to the same place, as autonomous beings born of the artist’s will. GK

Ricardo Cinalli (Argentina, b. 1948). The Owl and the Crow, 2018. Mixed media: oil on paper mounted on canvas and diamonds, 245 x 110.

Ricardo Cinalli presents Pallas Athena as her ancestor and patroness of Prossalendi’s Britannia. Here the goddess is inspired by the larger-than-life statue kept in the Archaeological Museum of Piraeus. On her head she wears raised her Corinthian helmet, which is decorated with owls on the cheekpieces. On her body she wears a long cloak and her aegis, wreathed with snakes from the head of Medusa, passes diagonally across her chest. In her right hand she holds an olive branch on which rests her dedicated bird, the owl. This is a bird of prey with a special vision that allows it to hunt in the darkness of the night. With her left hand she supports a pole from which the British flag hangs. The end of the flag is held in the beak of a crow, which in the artist’s view symbolises Britain. Tending to collect whatever shiny thing captures its attention, this feature could perhaps refer to Britain’s imperialist past. The perception of the composition is theatrical with the Ionian Sea as background. Athena is rising on a circular platform that refers to Corfu, while her flagpole invades the circular opening on the roof, in the form of Selene, from which the light comes. The darkness of the nocturnal landscape contrasts withthe scattered diamond stars and the halo of the chaste goddess. MR

Milly Flamburiari (England). Britannia in Corfu, 2018. Oil and ink on board (96×96).

Being British with a touch of Hellenic ancestry, Milly Flamburiari takes the subject of Britannia as an opportunity to look at her Classical roots. With the imagination that characterises her work, Milly gives Britannia the looks af an ancient Greek goddess, dressed in a white chiton wearing a Corinthian helmet and supporting Poseidon’s trident and her shield decorated with the Union Jack. She is centrally seated on a cluster of canon balls over the three zones of waves in successive styles ranging from abstraction to naturalism – stylised monochrome waves evocative of the seabed, the sea proper peopled by polychrome fish, and as seaway surface for a pair of frigates. With her Britannia, the painter sets out to make certain points, which embody her emblem’s spirit. As the sun rises from the composition’s centre, its rays gather strength and grow bigger and brighter. This symbolises Britannia, the embodiment of Great Britain’s ever-growing influence, casting its rays like the sun, far and wide around the world. With her dominant naval forces, Britannia conquers the seas, while at the same time she has an inscrutable smile on her face and holds a sprig of olive, signifying humanity’s aspiration for peace. This painting is envisaged as two separate worlds – the upper portion of the work with its strong red white and blue colourway of the Union Jack; and the lower portion, the forceful blue and white of the Greek flag. Thus united, the two nations meet to celebrate this historic happening. This painting serves well its purpose of offering viewers a feast to their eyes. MR

Dimosthenis Gallis (Greece, b. 1967). Exit, 2018. Giclée print on photographic paper, 50 x 50.

Wearing the white suit of Pallas Athena, designed by Dionysis Fotopoulos, Britannia rests exhausted on the back of the Lion who stands staring at us, with disarming shyness and wonder, in a space reserved for disabled people in a rather forgotten and wet car park. In the “Exit” photographic work Dimosthenis Gallis sets up with actors and theatrical props a scene of historical utopia with excellent attention to plausibility. His technique allows him to harness every Lion and prescribe every truth. Britannia in his hands disputes her own identity and avoids looking at us as if she has lost faith in herself, presenting her difficulty in adapting to the new circumstances of our time, adhering to the memory of her golden past. The loneliness of the space seems to suit her escalating introversion. Although on the wall there is the word “EXIT”, with an indirect reference to the recent Brexit referendum, the claustrophobic feeling that characterises the whole scene hints at exactly the opposite. The irony is obvious: the way to the exit, given the decision that British citizens finally made, is in reality a deadlock. Emphasising the challenge, the photographer places Britannia’s trunk in front of the “X”, deleting and totally cancelling its essence and indicating that the decision is disastrous. By contrast to the visual allegories and the messages of the artist, the composition is governed by volumetric robustness and sculptural clarity, making direct references to the artistic spirit of Prossalendi as a top neoclassical sculptor of the 19thcentury; the photographer gently respects his principles and teachings and introduces them methodically into his work. IA

Nikos Giavropoulos (Greece, b. 1971). Britannia, 2018. Plexiglas, resin, acrylics and spray on wood, 70 x 100 x 3.

Nikos Giavropoulos exhibits the Union Jack along with Athena’s head and the most typical medieval Gothic knocker of a lion head. These two emblems of Athens and the United Kingdom are spread over its flag. The flag itself stands for unity, Athena for wisdom and the lion for power. Yet, one does not fail to observe that the heads as well as the knockers are spread over the Union Jack and are made from resin. Furthermore, chromatically the heads range from white to red, while the knockers from light to dark blue hues. The Union Jack itself is not presented in its original colours but in an almost monochromatic approximation of them; it seems more an appropriation of the flag than the flag itself and is thus reminiscent of Jasper Johns’s 1954 American Flag that gave the critics the dilemma whether his painting was a flag or a painting of a flag. The way the emblems are set up, their material and colours give the viewer the impression that Giavropoulos employs the national emblems for what they are and how they have been appropriated by popular culture, fashion and consumerism, thus creating a dilemma for his viewers analogous to Johns’: are these emblems real or are they parodied copies of themselves, as in the case of the Sex Pistols? CP

Ken Howard (England, b. 1932). Prossalendi’s Britannia, 2018. Oil on canvas, 120 x 100.

Ken Howard is offering us his own version of Prossalendi’s Britannia, bearing the same title, with the outstanding painting quality that characterises his work. The high level of his drawing, his tonal precision, combined with historical referencing, combine to make a work of great importance. The feminine depiction of Britannia, as a dynamic ruler of the sea, is explored in terms of its evolution through time. The artist chose to use as a reference a classic representation from a chromolithographic advertisement for the “British Isles March” published by John Blockley of Argyll Street, London. Morphologically, the composition has been reversed in order to restore the elements of the work – Britannia’s figure, trident, shield and sailboat in the background – as they were according to the lost sculpture which adorned the palace of St Michael and St George. The work also notes the connection between the form of Britain and the way that ancient Greeks had chosen to symbolise wisdom and power, in the face of the female goddess Athena. The second reference of the work lies in the representation of the seated lion, which is based on the celebrated monument of Pope Clement XIII, located in St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. This monument was created by Antonio Canova, the most prominent sculptor of neoclassicism and also Prossalendi’s teacher. The artist’s British descent is what helps him capture the importance of tradition, ideas and values for the people of his country. Through the combination of these two historical sources, the artist pays homage to the exhibition’s theme. He succeeds in indicating the weight of Britain’s history, and through his work’s symbolism, he means to celebrate the cultural exchange between the British and Greek nations. GD

Marion Inglessi (Greece, b. 1961). Disambiguation, 2018. Acrylic on paper mounted on plywood, 30 x 82.

In her work Disambiguation, Marion Inglessi makes a contemporary political and social commentary with references to the age of Imperial Britain and its artistic production emerging from the Industrial Revolution and the economic development resulting from its colonies and possessions. At the same time, using all of the distinguishing elements of a typically British sophisticated technique of representation for urban use, the artist organises a flow of three unconventional sequential images that are in direct contrast to the urban culture representative of this technique. The work develops as a triptych in a neoclassical frieze that deliberately imitates the impression of British Wedgwood porcelain, and especially the Jasperware type in particular, which was created to look like ancient cameo glass. The version that the artist consciously reproduces is referred to as Wedgwood Blue and has white figures and floral decorations in relief that she carries in her work as repetitive decorative motifs running along the top and bottom as well as trees separating the three scenes. The entire composition alludes to the still-frames of the cinematographic perforated film. The seemingly idyllic picture of glory of the first still of the ancient Greek-inspired Britannia with the mighty lion under her tender gaze, is succeeded by a picture of the lion’s sudden attack on the terrified Britannia, and ends in the last still with the lion in repose and the total absence of Britannia. The artist refers in her work both to the uneasy coexistence of the British Empire and its various colonies, protectorates and possessions—the Ionian Islands included — as well as to the traces of the memory we retain today of the imperialist sovereign power represented by the lingering lion of the third still and the totally absent Britannia of glamour, renown, and glory. IA

Yanna Kali (Greece, b. 1981). Through Prossalendi’s Gaze, 2018. Coloured pencils on paper, 35 x 50.

Yanna Kali puts the focus of her search on the personality of Prossalendi himself, as it was formed between the two countries, Greece and Britain. His thought and action as an authentic pioneering artist in his heyday are revealed by the symbolic gaze, which we are called to face. The cultural link between Greece and Britain, which drew the catalytic sculptural group of Pallas Britannia from the iconography of the previous epochs, focuses on the depiction of the bridge at the centre of the waving flag of Britain. The cross of the flag has admitted a hole that leads the spectator’s gaze to the endless shore, one step closer to the white-blue landscape, implying the Greek flag. With simple illustrative means and with the characteristic element of the binary and the doubt posed by her works, the artist invites the viewer to clarify where on the opposite bank does s/he stands. Does the flag of Britain mark the “here” and “now” or does it announce the “there” and “then”? The decision is a personal matter for the viewer, who is asked to investigate for the thought of Prossalendi in time and to wander between the two identities, which in such an elaborate way became one in his consciousness. GK

Stella Kapezanou (Greece, b. 1977). Brittany’s Back Yard, 2018. Oil on linen, 210 x 180.

The work of Stella Kapezanou presents the elements of a pure and unapologetic painting. Responding to Prossalendi’s Britannia she renders a contemporary version of her, in which the symbolisms of the past have turned into modern depictions. As the title of the work implies, we find ourselves in Brittany’s back yard. Witnessing a rather private moment, we see her sitting on the Union Jack’s flag-towel, passively holding a glass, a substitute for the trident, being served champagne by a youthful man, who resembles the classical prototypes. A stone pillar, very much like a third presence in the party, lies collapsed, hidden, like ruins of the ideal. There is a sense of ambiguity coming from the surrounding elements of the background, which seem to be acquiring an entity of their own. Grand yet simple, the villa appears deliberately defective, forgotten in a past time, so as to turn the viewer’s attention to what is taking place in its foreground. The offer and acceptance of the man’s ‘precious’ liquid is reflected on the surface of the pool, as an indication of the semantic and temporal fluidity in all things human. The almost-naked bodies are associated with the simplicity of the villa and the naturalness of the surrounding vegetation, altogether, innocent and fragile, compared with the spiritual. Throughout the work, there is a dominant repetition of a dual interpretative scheme, that of literalism and metaphor. This depiction seems very realistic and fake at the same time. It gives us the feeling of a recovered paradise, where power and recognition, have led people to a kind of eudaimonia that hypnotises or awakes through its exaggeration. The artist’s purpose is not to comment on the present image of Britain, but to present a personal observation associated with the typical depiction of Prossalendi’s Britanniaand let the viewers exercise a social critique through self-reflection. GD

Aris Katsilakis (Romania, b. 1974). Finding, 2018. Terracotta and wooden box, 70 x 50 x 54 / 80 x 50 x 60. Courtesy of Alma Gallery, Athens.

Aris Katsilakis explores the impact of human intelligence on the material world, the drive that is the guiding principle of civilisation. The forms from his familiar environment are reconverted into unexpected encounters between them. The hybrids, carriers of the material that he creates, are the mysteries of a potentially existing world. Prompted by the lost sculpture of Paulo Prossalendi, he creates a plastic narrative with ambiguous conceptions, which are left to the viewer’s mind to be interpreted. The composition expresses the fantastic story of a find, a splinter of a lion sculpture, the British symbol, of timeless and landless origin. The fantasy find has ceased to be the subject of the archaeological excavation and is defined as an item in conservation, which will soon be a museum exhibit. The narrative of the course of the material object, from a work of art to an object of cultural management, is captured in the same material form, in an eloquent and clear way, by touching the logical fluidity, in full analogy with the malleable material of the clay, that the manages. The artist’s quests bring back to the fore the reflections on the role of the artist as a subject of history. In the Finding, the dominant ambiguity of the elements exacerbates the visual negotiation. The coexistence of the tools for the preservation and transport of fragile objects with the punta, the main tool for the transfer of the gypsum prototype to the marble, skilfully evokes the artist’s presence to the viewer and underlines the origin of the poetry of the material document. GK

Harris Kondosphyris & Panagiotis Kyratsis (Greece, b. 1965 & 1968). In Wonder Woman We Trust, 2018. Three-dimensional digital clay modelling, 40 x 34 x 19.

Harris Kondosphyris, Professor at the School of Fine Arts of the University of Western Macedonia, Florina, in collaboration with Dr Panagiotis Kyratsis, Professor of the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Industrial Design of the Technological Educational Institute of Western Macedonia, collaborated on an idea about the status of Prossalendi’s Britannia, missing from the Palace of St Michael and St George, Corfu, since 1864. The professors opened the topic in a discussion with their students, which ended up in a collaborative work that their group produced (Orestis-Antonis Aufheimer, Nikolaos Efkolidis, Anna Kampouridou, Athanasios Manavis, Prodromos Minaoglou, Kyriaki Plaka and Agisilaos Rompolas). In an effort to arrive at a propagandistic understanding of the world, Western man inspired the fantastic story where modern superheroes attempt to redefine justice and re-establish power. Prossalendi created the statue on the order of the British High Commissioner on the basis of Britannia being the successor to Pallas Athena with the Lion as a descendant of the one in Nemea, and Phaeacian Boat as an emblem of the British supremacy at sea. Nowadays, in the light of postmodernism, the subject is updated with the Wonder Woman standing on a bundle of banknotes with a helmet in a ‘selfie’ position, surrounded by two mechanical dogs. The title is an ironic reference to “In God We Trust”, the official motto of the United States of America. MR

Alexandros Maganiotis (Greece, b. 1972). The Secret Geometry of Seven, 2018. Acrylics on mylar and transparent film, 155 x 120.

Alexandros Maganiotis’ Secret Geometry of Seven develops on two levels each representing a different era and a distinct political perception. The inner level presents the era of Imperial Britain, which appears crowned with a classic Greek antefix and dominant over its colonies and possessions that include the Heptanese. All the supreme symbols are represented by iconography: the mighty lion, the medals of glory, the peace-bringing olive branch and her worldwide dominion of the sea, all of which preserve and enhance its glamorous global glory. Even the anniversary stamps quoted by the painter glorify the British generosity at the moment when she offers the entire Ionian State offers as a wedding gift to King George I of Greece. The seven Ionian Islands, the tips of a regular heptagon, lift Britannia’s height and create the primordial design, which the artist presents as an honorary reference to the sculptor Prossalendi. All the symbols and elements glorify the eternal glory and majesty of an empire that did not perceive the moment that at the turn of time all sovereign data can be overthrown and the years of the mighty empire remain only a subject of historical study. On the external level, the artist transfers his visual composition to modern times by demonstratively defaming the image of Imperial Britain from a rushed black graffiti (here censored) that a subversive spirit of voluntary isolation imposes new ways of life and introverted visions of living together with the European and the global community in direct contrast to the dominant model of expanded British sovereignty over the last centuries. IA

Georgia Matsamaki (Greece, b. 1971). Laion, please come back to the boat!, 2018. Collage with cut-out printed paper and beads, 21 x 30.

With theLaion, please come back to the boat!collage Georgia Matsamaki organises a surrealistic scene of historical madness imbued with acute truths and critical humour. The scene is structured with strategic accuracy and intelligent bipolarity. All the pictorial elements that refer to the given subject of the exhibition are present and are communicated either by metaphors or by allegories, in a climate of bittersweet Dadaist sarcasm. The half-naked Britannia with all its military equipment travels to exotic places with parrots and seagulls, apparently on the verge of its tropical possessions. Naturally, aboard the HMS Foxhound the peacekeeping olive tree is transported at the same time as her cannon. Her sovereignty results one way or another. Her enthusiasm for Greece is unquestionable. Corfu is in her mind and her appetite for classicism in her helmet. Only the mighty “Laion” (Lion) needs her admonition to return aboard the safe ship from the wet and dangerous loneliness on the islet where he chose to find privacy. The artist’s mirror-like distorting humour here has taken off in an ironic delirium. She has consciously replaced the roles of Britannia and the lion with the respective roles of Europe and Britain in the current Brexit era and the encouragement to re-enter the pattern of United Europe echoes in our ears: “Britain, please come back to the European Union, or else your little paws will get wet!” IA

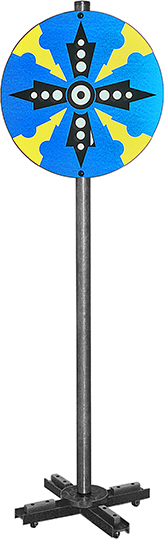

Dimitris Merantzas (Greece, b. 1967). Multi-Directional Possibility – Danger of Disorientation, 1996. Iron, aluminium, reflective stickers and wheels, 212 x 65 x 50.

Dimitris Merantzas displays a three-dimensional object that is part of his 1990s Imaginary Signs series. The title of the work is Multi-Directional Possibility – Danger of Disorientation. The artist draws inspiration from real road signs and employs the materials and techniques of road signs for his imaginary signs. Road signs have standardised global information codified in certain ways in order to be immediately readable and understood by drivers. Merantzas explores the possibility of using such standardised information for more personal choices and processes of self-reflection and awareness. Could these signs manage to direct our constant need for self-analysis and awareness? This is a very interesting question that the artist addresses to his viewers and it is up to each viewer to answer. However, the particular imaginary sign he selects to display in an exhibition devoted to Prossalendi’s Britannia, and through which he celebrates the relation between Britain and its past protectorate Corfu, carries some additional meaning. Merantzas eloquently and clearly voices the concern of many Europeans about the fate of United Kingdom after its divorce from the European Union. This fate seems indeed to be marked by multiple directions to an extent that there is really a danger of disorientation. CP

Alkistis Michaelidou (Greece, b. 1959). Peace, 2018. Charcoal, chalk, dry pastel and oil on canvas, 70 x 100.

With Peace, Alkistis Michaelidou builds a bridge of subversion between the 19thcentury of Prossalendi and today’s imperative demands. She organises her visual world on two levels of painting, each of which represents a different era of aesthetic, social and political ideologies. On the inner level, the painter imprints the monumental sculptural complex by Prossalendi of Britannia as Pallas Athena along with the mighty Lion, while giving the Phaeacian ship’s prow a classic spirit of glory and honour. In the details of the composition, the painter deviates from the beaten track by transforming the finial of Britannia’s trident into a linear sign of peace that is raised vigorously and aggressively towards the sky, allowing it to be reflected as a circular label in her shield. The special design mutations, which the artist engineers in the composition of Prossalendi, allow the conceptual extension of her social aspirations to the next level of painting perception that she organises on the outer level her work. There she focuses on the task of giving the opportunity for the viewer to sneak into the neoclassical 19th century through a circular transparent scuttle, which may be the mouthpiece of a sea monocle of close observation. And the desecration is written in thick, doubly-inscribed red graffiti letters “PEACE”, on the absolutely necessary tool of seafaring dominion of an empire based on the sea, the world trade, the constant exploratory journey and the imposition of weapons for the preservation of its power. The most violent way of writing translates into the world’s most affluent demand of life. The artist with a spirit of communion and a post-academic manner transcends the space-time codes of demands by combining the spirit of Prossalendi with the constant necessity for peace. IA

Nicholas Moore (England, b. 1958). Remember me, 2018. Mixed media on paper, linocut, glitter, gouache, film, 93 x 66.

Nicholas Moore manages to merge together modernity and historical tradition, in a pop and playful manner. The focal point of the work is a shrine like those built on the road in memory of lost ones, a commonplace in Greek culture. In the position where a religious icon would normally stand is a map overpainted with Prossalendi’s Britannia, wearing her Corinthian helmet, decorated with daffodils, a flower directly linked with Greek mythology. The candle inside is lit, as if trying to keep alive the memory of the lost statue. The roof-like top of the shrine, resembling an ancient temple, carries the heraldic symbol of Britain that coexists with the owls, which symbolise wisdom. At its base, there is a dedicatory inscription, phrasing the well-known “Rule, Britannia” in Greek, which celebrates the country’s maritime supremacy. A hidden message awaits the viewers of the work near the trident, resting on the shrine’s side. It is obvious that the artist has a strong personal connection with his artwork, something that can be verified by the coexistence of numerous Greek and British symbolisms, as well as the musical and linguistic references in the background. Within the black frame, we encounter an assemblage of drawn elements. These perforated shapes portray pieces of the Meccano construction game. One could say that these pieces take after ancient symbols of good luck, and if they were to be connected, they could create a deus ex machina structure. An important element of the work is the phrase “Remember me, but forget my fate”, a reference to Henry Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas (1689). The phrase, which is also the title of the work, is used to create an allegory, paralleling the loss of Britannia with the nation’s loss of identity. Lastly the phrase “I don’t belong here” is connected with the feeling of segregation and not belonging, as a result of the latest political changes in the country. GD

Konstantinos Pardalis (Greece, b. 1977). Still ON, 2018. Mixed media, 47 x 42.

Konstantinos Pardalis starts with Britain’s self-identifying reference as “Brit Athena”, to describe the political presence of the country in the present time. Starting from the emergence of the “in-between space”, as described by Michel de Certeau, in which potential practices become reality, the artist sets as a reflection point our current perception of the future of world history. The potentially functional use of a ready-made object and the visual elements that make up the conceptual intake of the work of art are clearly described, thanks to the intelligent iconography and the careful composition. In Still ON, the goddess of wisdom has been “dressed” with the distinctive red colour of the British flag, with the stars of Europe framing it, obeying a visual writing, with clear references to pop culture and attitude. Britannia, as the artist himself points out, is presented “as a catalyst, as a revolution that marks the denial, the rebellion and the subversion” of the deterioration and decline of humanity. The role of British intelligence in the chronicle of history is matched by the choice of a light source switch, placed in the centre of the composition. Its appropriation, with all its connotations, unleashes the dual light-darkness relationship, from which the opposing pair of progress and unremitting regression towards obscurity emerge semiologically. Placing the switch in the ON position leaves the viewer in no doubt about Britain’s contribution to the history of culture and the development of the whole of Europe. The question is – what happens if the switch is turned off? GK

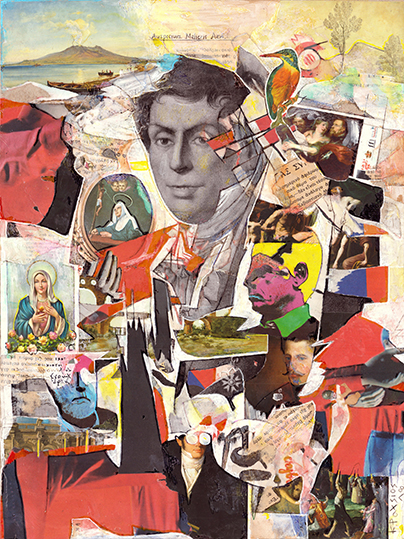

K. N. Patsios (Greece, b. 1977). Auspicium Melioris Aevi, 2018. Collage on paper, 40 x 30.

K. N. Patsios creates a collage on paper entitled with the Latin motto of the Order of St Michael and St George, Auspicium Melioris Aevi (Token of a Better Age), which in a free translation means – the best is yet to come. Right underneath the Latin inscription, the artist sets up the portrait of Paolo Prossalendi whose face dominates the composition. Then in the fragmentary picture, the viewer can see the image of the Virgin Mary, Santa Rita the Patroness of Impossible Causes, the face of Plato, who influenced the whole Renaissance, along with Canova’s, who was Prossalendi’s teacher, a tropical bird, a work by Caravaggio, another one by Domenikos Theotokopoulos (El Greco) and a third by Paolo Veronese. What unites these disorderly strewn elements is Britain itself and the several cultural sources of its past that make this particular European nation what it is today. The artist alludes to the neoclassical constituent of British history that was prominent and active in its imperial past, particularly during its colonial apogee in the 19thcentury. Does this past carry an omen; a pledge that the best is yet to come? The artist’s messy arrangement of elements seems at first to entail a negative answer. At second glance however, the idea emerges that historical memory is essentially fragmentary, and it suffices for one to put this memory in order through education so that one can take advantage of this rich and fertile identity. CP

Aglaia Perraki (Greece, b. 1966). Athena as Britannia on the Rock, 2018. Egg tempera on canvas, 150 x 100.

Aglaia Perraki exhibits a banner presenting, as her title indicates, Athena as Britannia sitting on a sea rock. The artist paints in a mixed media egg tempera technique a contemporary, young Greek woman, wearing a long white dress, with her hands set on her knees and a look on her face betraying the determination of youth. The calm sea background contrasts with this determination, reflecting the colonial past of the United Kingdom, which with the naval superiority of its fleet governed a great part of the globe, in the course of 19th century. The artist paints a golden sky reminiscent of the metaphysical background of Greek orthodox icons, conveying majesty. The composition is obviously inspired by the sestertius of Antoninus Pius (138-160 AD) from 150 AD, which became the basis for the subsequent 1672 farthing of Charles II. There is an inscription at the bottom of the composition that reads: “One is the principle. At the edge of the great razor, the mirror crumbles.” The motto seems to refer to the razor of youth or rather youth as a razor, which is capable of overcoming the greatest obstacles, even the ones that have to do with the image we have about ourselves, through the mirror of our soul. At the same time, it is a motto that matches the mighty power and global rule of Britain in the past. CP

Artemis Potamianou (Greece, b. 1975). I thought you knew my story, but not anymore, 2018. Installation: spray on plaster, 45 x 50 x 60.

Artemis Potamianou sets up a heap of female heads, which originate from classical antique statues of Athena and other women deities of various sizes. Piled one on top of the other, in a seemingly accidental fashion, these heads are arranged in a heap in the corner of the room, where the walls intersect, recalling thereby Joseph Beuys’ famous 1960s Rostecke (Rust Corner) pieces standing on corners. Beuys himself borrows his arrangement of Rosteckepieces from suprematist hangings of monochromatic squares at the intersection of two walls uniting design, sculpture and painting in the quest of an altogether new way of relating to creation and society. Potamianou follows Beuys and suprematism with a corner heap of sculpted heads, obviously mass-produced on an industrial scale as tourist souvenirs. Her heap of heads undermines the unique classicist sculptural object by pop artistic repetition. Her gesture of amassing the decapitated heads makes thus an ironic reference both to classical and modernist sculpture. The classicist heritage today is erratic and is mediated by popular culture and the tourist industry. However, as her title indicates, there is more to the story of classicism, perennially told and very often misunderstood and distorted. The reception of classicism in the United Kingdom is one of these stories that need to be explored anew in light of the many fragments that still exist scattered all over Britain, testifying this reception. CP

Natassa Poulantza (Germany, b. 1965). The Britannia Wreck, 2018. Digital print on canvas, 85 x100.

Natassa Poulantza presents a digital print on archival paper. The work is a photographic image, which has been manipulated by the artist and is now composed of vertical strips. The image conveys the atmosphere of a seascape under water, and this may indeed be confirmed by the title of the work, The Britannia Wreck. The work is accompanied by the artist’s narrative: “Conceiving of the work in the world of propaganda, provocation and fabricated fake news, we may assume that Prossalendi’s Britannia statue is the sole sculpture that Damien Hirst did not discover, retrieve or present in his latest monumental exhibition with works by the collector Amotan. Despite the fact that the digital work I present consists mainly of photographic material of a professional diver and treasure hunter, I must disclose a mysterious detail: when the underwater antiquities personnel discovered the spot that the professional photographer and the experienced diver had indicated to them, the statue was no longer there. No matter how much we enter the world of metaphysics, we could risk asserting that we have to do with an amphibious ghost statue, which moves with ease in a space-time void or hole.” Artists do tell stories and Poulantza seems to wish to communicate hers. It does not matter whether the story corresponds to reality as long as it entails a certain awakening and position in the face of present time and history. CP

Irene Pouliassi (Greece, b. 1989). Trident Respawned, 2018. Aluminium, iron, leather, hair and teeth, 200 x 70 x 5.

Irene Pouliassi creates her visual precept for Pallas Britannia, with the spear of the goddess Athena transforming into a trident, giving a new twist to the mythical encounter of Zeus’ daughter with Poseidon. The victory of wisdom and strategy over the seven seas of the world is a comment on the power of Britain over the centuries, giving the spear the second reading of sceptre. The trident-sceptre, deleting the form of the characteristic cross with the diagonal strips, is placed vertically, with its extended finial being bound with human hair and teeth. The work Trident Respawned addresses the issue of history as a case of personal mythology, which incorporates over its course the quintessence of human existence and, at the same time, is determined by it. The artist elaborately reveals Britain’s life-giving force, which has long been the driving force towards the avant-garde. The elaborate wrapping of the sceptre with the courteous offerings, as sacred devotion, not only reflects the unshakable dedication of the people, but reveals the attachment of their existence to the history of the country on the road to eternity. The rebirth of Athena’s spear follows the path of the dedication of the people who protect the sceptre and who devote themselves, like in a ceremonial rite. The dedication of one part of oneself symbolises the emergence of a new subject and its definitive change, with the artist marking the transformation of Britain itself another aspect of the ritual. GK

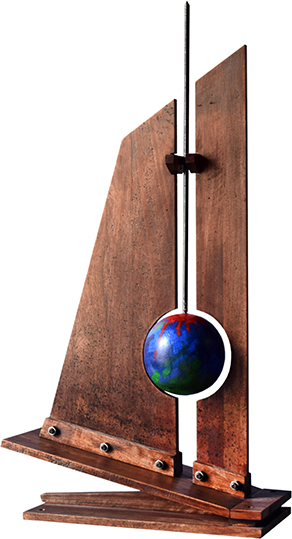

Vagelis Robolas (Greece, b. 1952). The Journey of Odysseus, 2018. Wooden construction, 100 x 70 x 25.

Vagelis Robolas draws from Britain’s naval tradition the dexterity and the strength of the people who roamed the seas and reached the end of the world, reminding us of the beginning of every impossible task. The Journey of Odysseusreflects the primordial need of man to confront the forces of nature, seeking ‘Ithaca’, the place of ideal utopia. Inspired by the legend of Odysseus’ journey from Phaeacia to Ithaca via the barca senza timone (boat-without-rudder), the artist gives form to the magical boat, which, without rudder and with thought as its captain travels faster than the hawk and always finds its way. Its wooden construction carries into its heart the globe of the earth, which has a dual reading, both as a compass, a geo-orientation tool and a pathway, as well as a conceptual perception of the world. The arrangement of the globe of the earth in the centre of the composition is also the addendum of the visual formulation and reveals the inner meaning of the boat-without-rudder, which the myth teaches. The symbolic arrangement of the imprint of the world is the projection of internalised desire to seek and conquer the endlessness of life itself. The psychic powers and virtues of the adventurous human nature have taken on the role of the rudder and are allied for the journey of Odysseus, the mythical hero, who as a timeless symbol represents the resourceful people of Britain. GK

Margot Roulleau-Gallais (France, b. 1986). What are we, Britannia?, 2018. Jesmonite, newspaper and bronze powder, 36 x 17 x 17.

In Margot Roulleau-Gallais’s sculpture, we recognise the figure of Britannia as goddess Athena, with reference to her representation in Paolo Prossalendi’s work as well as the British 2 pounds coin. During her creative process, the artist casted the sculpture using pieces of newspaper, with texts of the country’s current affairs. A burst of words makes up her body. On the head she is wearing the Corinthian helmet, in her right hand she holds the trident, while on the left she holds the shield, which carries a relief portrait of Prossalendi, reinforced with bronze details. Her figure seems to be emerging from the turbulent sea with the waves becoming the garment that covers her. The presence of the lion that usually accompanies her representation, in this work is implied in the form of a written word, at the place where it would normally stand. The newspaper cut-outs are chosen for their key-words which serve as visual references of political contect throughout the sculpture. The work is inviting its viewers to read it both visually and verbally. The chromatic details that the artist added refer to the original colour on ancient Greek statues and as palette reference the colours of the Union Jack. It is the artist’s will to pay tribute to Prossalendi as an artist who elevated the sculpture of the period and pioneered in bronze casting. Her love for classical sculpture education makes this work dedicatory. One could grasp it as gratitude for apprenticeship in the work of Prossalendi, in which she follows his teachings and imitates his technical avant-garde. GD

Dimitris Skourogiannis (Greece, b. 1973). Lady Lace, 2018. Mixed media: wood, ceramic tiles, newspapers, paper and acrylic, 160 x 60 x 30.

With the Lady Lacy work, Dimitris Skourogiannis attempts a reference to neoclassical 19th-century sculptured portraiture as an extension of Prossalendi’s artistic creation that was realised within the expanded British sovereignty. Lady Lacy is a fragile, tender sculpture with soft, humble materials that, while creating a direct contrast to the gravity and monumentality of the materials of the traditional sculpture, such as marble and metal that gave Prossalendi the ability to create his personal world of sculpture, in fact carries the sculptural insight of the 19th century into the contemporary era. The artist places a rose on a part of his composition and introduces the dimension of time and the ephemerality of seasons into his work. Thus, he declares the days of bloom, achievement and glory, but also the days of decline, contraction and withering. Wishing to further enhance the sense of volatility, the sculptor presents a collection of ceramic tiles and a string line level, making direct reference to the processes of construction but also the treatments of demolition. The extensions about the cycle of climax and decadence that the artist stresses relate not only to Britain but also to every empire that first shone and then disappeared from the face of the earth. With the paper lace and the general spirit of his sculptured composition, the artist introduces us to an urban Victorian environment and reminds us of the trend of leading modern sculptures, such as Degas par excellence, to import real, fragile and lived materials into their sculpture with a reference to the temporality and vanity of existence. So temporal and brief was the presence of Prossalendi’s Britannia monumental complex, which for less than half a century decorated the palace’s façade, and then was lost forever. IA

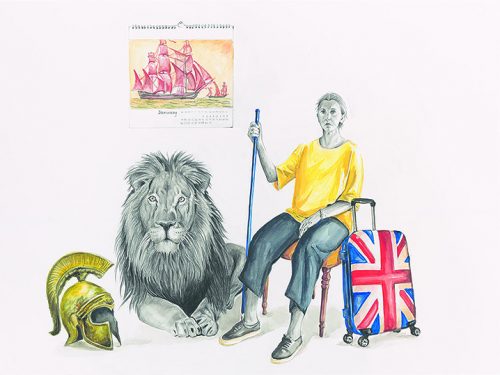

Anna-Maria Smyrnaki (Greece, b. 1971). Great Britain, 2018. Pencil and watercolour on paper, 90 x 120.

Anna-Maria Smyrnaki defines Britain in the context of contemporaneity and approaches her as a country of destination, research and expectation. Inspired by Paolo Prossalendi’s Britannia sculptural complex, she redefines the composition in contemporary terms. The painting displays surreal elements, which are specific to a paradoxical encounter, with multiple symbolism to read. The goddess Athena has given her place to a mortal bourgeois, resident of the modern world, with the vigour of her youth lost and time having left on her face the signs of wisdom and the experience of life. The history of Britain is present in the composition and as a dominant influence is aptly placed at the highest point of the composition, in the form of a calendar purchased on an earlier trip. The depiction of the scene, in an intimate living room, with the intimacy of everyday objects, gives immediacy to the painting’s contents. The seated woman looks forward to the journey with her suitcase ready and her gaze firmly facing the viewers, claiming their attention with the determined posture of her body and the walking stick in her hand. The paradox of the work begins just next to her with the arrangement of Britain’s symbols. In the revised representation, the lion has come to life and lustfully lies by the woman’s feet as just another cat, posing questions about the relationship between them. The singularity of the composition is intensified by the erstwhile helmet of the goddess Athena lying on the floor, creating a mystery between the identities of the woman and the object, and how they relate. GK

Aris Stoidis (Greece, b. 1971). Prossalendi’s Britannia Now, 2018. Maquette: paper and wood ink, 30 x 40 x 1.

Aris Stoidis presents the work entitled “Prossalendi’s Britannia Now” – three-dimensional folded paper on which the design of the Union Jack is painted. The composition includes a standardised crowned figure of Athena, holding a spear, next to the British flag and the Lion, an old symbol of imperial Britain. Folded paper was predominantly employed in the context of synthetic cubism and collage at the beginning of 20th century in an effort to conflate sculpture and painting as well as to make art ‘life’ and ‘real’, avoiding the illusion of representation via the Renaissance convention of perspective. The artist is faithful to the cubist vision as he also employs ‘real’ elements such as human hair and metal in order to increase the degree of reality conveyed by his work. The artist seems to wish to recompose not only Prossalendi’s lost statue but also to furnish those ‘real’ elements that the statue stands for, namely the allegiance between Corfu and Britain, between the protectorate and the colonial power, via art. Is the message of this allegiance between Britain and Corfu better conveyed in the modern vocabulary inspired by synthetic cubism and collage rather than in the illusionary mode of neoclassical or romantic artistic depiction? This question that the artist addresses to his work’s viewers clearly merits an extensive and systematic review. CP

Shubha Taparia (India, b. 1975). Britannia at Tenterden Street, 2018. Lenticular print on 3 wooden palettes, 112 x 80 / 3 x (10 x 120 x 100).

Undoubtedly, the work of Shubha Taparia bears the characteristics of a contemporary art, combining her personal artistic vocabulary with ingenuity. Her aim is to restore the image of Britannia and extend its journey beyond the story known to us. In order to achieve this, she uses a specific printing technique that brings the illusion of motion to the work. The so-called lenticular effect, which is made up of layers, becomes the medium and the message of the artist’s project. This particular piece is based on a series in which she explores locations under reconstruction and lifted objects. According to her, in this aspect of urban life, the process of suspension can transform immovable objects of large scale into flying, enigmatic forms. In her work, she presents a sculpture similar to Prossalendi’s Britannia, which adorned the Palace of St Michael and St George in Corfu, suspended over the undefined cityscape of a building under construction, at Tenterden Street in Mayfair, London. The artist is suggesting a follow-up to the story of the disappeared sculpture, placing it in present time, returning it to public view. The back and forth movement of the sculpture in the moody sky symbolises its journey through history, while the seeming sloppiness in its transportation forecasts its loss. The repetitive movement, which is activated by the shifting gaze of the viewer, refers semantically to a predetermined state. Britannia becomes a pendulum, which measures the cyclical course of the rise and fall of urban centres as well as the transient interpretations that cultural objects acquire, even when they are lost or their notions devalued. GD

Yorgos Taxiarchopoulos (Greece, b. 1972). Double Face, 2018. Digital collage on paper, 39 x 27.

The detail of Prossalendi’s Britannia from a historical photograph is the beginning of Yorgos Taxiaropoulos’ creative act. Through the artistic gestures that strengthen the meaningful link of elements with straightforward references to the history of Prossalendi and contemporary British and Greek reality, the artist composes, using collage, a personal view of the cultural proximity of Greece and Britain. The sculptural complex of Britannia is inverted and placed semiologically as a section on the composition, defining it at two different levels, which describe the meaning of the work. The contemporary iconography rivals the historicity of the sculpture, which was to be lost in time but was intended to serve as a firmly-based tie between Corfu and Britain. The double face (double sided), a French term in clothing, is adopted as a pun, indicating the ambiguity of the work of art, with direct reference to the past that modern history embraces. The conceptual journey begins from the depiction of the Pallas Britannia and reaches to today’s age to draw the new image of the country as it is shaped by the mass media and establishes its image in the world consciousness. The inverted image of the sculptural complex expresses not only the time distance between the periods represented by the selected elements of the composition but also the mirroring between the real picture and its image, as is the case in Britain and the management of its projection by the international press. GK

Olga Tobreluts (USSR b. 1970). I Love Britannia and Britannia Loves Me, 2018. UV print on perspex mounted on forex, 120 x 82.

Olga Tobreluts creates a photographic print of Athena that she entitles I Love Britannia and Britannia Loves Me. Her work is clearly related to her Models series from the early 1990s when she created a series of works based on antique sculptures that she brought to contemporary life by giving them life-size bodies and dressing them in current fashion brands. The work bears the strong mark of appropriation, an artistic practice that was prevalent in the 1990s mainly in the USA but also in Europe as a result of the tendency to reconsider the artistic past and heritage in the general context of postmodernism. The image of Athena that the artist produces is one of flawless beauty and youth; it is an image that is at once associated with classical sculpture, since it is an amalgamation of beautiful facial traits and does not recall any particular face. It relates also to the postmodern pop artistic cult of beauty, as for example presented in the photographs of Pierre et Gilles. The artist’s reference to Joseph Beuys’ historic 1974 performance I Like America and America Likes Me is ironic and stresses the analogous love-hate relationship between Russia and Britain. Her title further indicates that there is mutual attraction between neoclassicism and Britain; Britain provided the fertile ground in which neoclassicism developed and sustained the culture and the physiognomy of a nation. CP

Amikam Toren (Israel, b. 1945). Armchair Painting: Rule Britannia, 2018. Ready-made painting, cut-out text, 61 x71

Amikam Toren approaches Prossalendi’s Britannia by activating his well-known series of Armchair Paintings, which he began in 1989 and continues to work on sporadically. In this recognizable series, the artist recruits various found objects and tries, with little interference, to transform them into conceptual works of art. He is interested in the attributed interpretation of the everyday objects he chooses, which are often overlooked or considered kitsch, and their new meaning when combined with the use of language. For him, it is an opportunity to provoke reflection and bring out the truth of things. This particular work is based on a ready-made painting. The painting’s sophistication is interrupted by the artist’s creative abstraction. The depiction captures an indistinct moment (is the sun rising or setting?) that becomes the surface on which the artist cuts out the text “Rule Britannia” after James Thomson’s patriotic poem of 1740. The line of the horizon highlights and delimits this phrase, while underneath it the turbulent sea seems to flatter and threaten it simultaneously. The use of this phrase is intended to provoke critical thinking, not only through its illustration but also through its verbal context. The font of letters used, being always the same in all the works in this series, implies that the sentence is presented as a quotation, without carrying the artist’s personal ‘voice’. The cut-out words are essentially present and made up from their empty space, a fact that comments on the semantic evolution of the phrase. Patriotism has been using it passionately to exalt Britain’s supremacy, however patriotism is also one of the reasons that led the country to Brexit, leaving the initial phrase to hover in a negative-empty space, thus absent in meaning. At the same time and on another level, the loss of meaning is also linked with the absence of Prossalendi’s Britannia. GD

Public Information

Exhibition: “Prossalendi’s Britannia” – Contemporary Perspective.

Supervised by Megakles Rogakos and curated by Ioannis N. Arhontakis, Georgia Damianou, Georgia Kourkounaki and Constantinos V. Proimos.

Opening: 8pm, Saturday, 1 September 2018

Duration: 1 – 29 September 2018

Opening Hours: 10.00am – 7pm daily, except Sunday.

Venue: Ionian Academy, 1 Kapodistriou & Akadimias Street, 49100 Corfu, Greece.

www.ionio.gr/en/prospective/university-history

Communication: Mrs Ioanna Anemogianni, +30 26610 87202, secretariat@ionio.gr

Visuals: www.corfuheritagefoundation.org/prossalendis-britannia-contemporary/

Reservation: Eventbrite

Accompanying Catalogue: A fully-illustrated 130-page catalogue, including an essay by Dr Rogakos on Prossalendi’s Britannia and comments on all the contemporary works by Mr Ioannis N. Arhontakis, Ms Georgia Damianou, Ms Georgia Kourkounaki and Dr Constantinos V. Proimos, is published by the Corfu Heritage Foundation (ISBN: 978-618-83770-0-4).