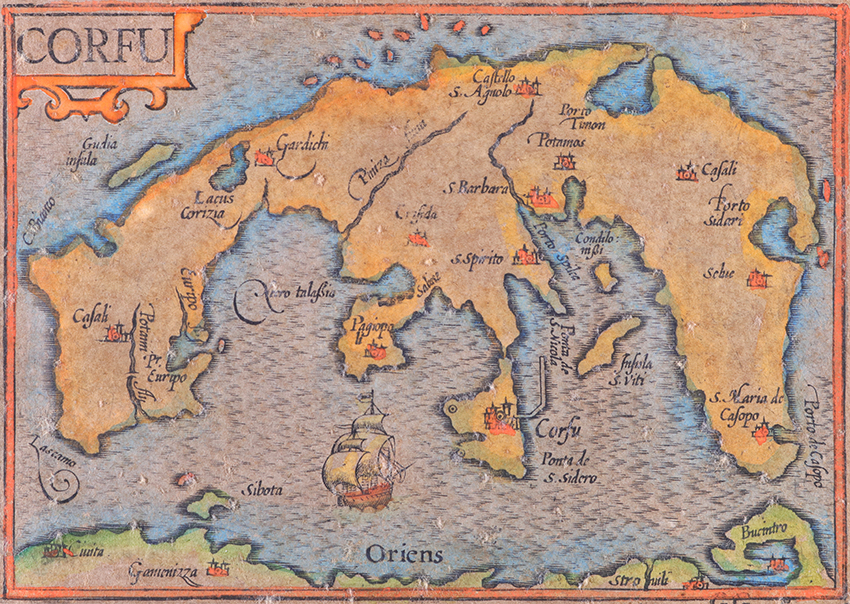

The French Occupation of Corfu – 1797-1799 & 1807-1814

By Frank Giles

On 8 May 1797, following Napoleon Bonaparte’s brilliant campaign in Northern Italy, the Venetian Senate signified its readiness to accept the conqueror’s terms. La Serenissima had politically ceased to exist and its empire lay open to the first taker. Napoleon was in no doubt who that should be. He always considered, to the point of obsession, that the Ionian Islands, Corfu principal among them, were the key to the Eastern Mediterranean and thus to the route to the Orient. Accordingly he hastened to take possession of Corfu and the other islands, employing the artful ruse of combining a French fleet with a Venetian convoy, the ships sailing under the Venetian flag.

When the fleet arrived at the end of June 1797 French troops, under the command of the Corsican general Gentili, were initially well received. Most of the population welcomed the promise of new liberties and an end to the power of aristocracy. These feelings did not last very long. The newcomers caused much offence by appointing two Jews to the Municipal Council, as well as by their disrespectful attitude towards religion, which included – horror of horrors – the mocking of St Spyridon.

Yet this first French occupation, formalised by the Treaty of Campo Formio’s transfer of sovereignty to France, brought some tangible benefits. In May 1798 the French installed in Corfu the first printing press to be known in Greece. They also abolished the feudal system, burnt the Libro d’Oro, laid down plans for improved education and substituted Greek for Italian as the official language (though this last edict had no particular effect until much later).

But none of this was enough to win the cooperation of the islanders, who soon discovered that these revolutionary French were just as penniless and just as inclined to impose taxes as the Venetians. When therefore Russia and Turkey joined the second coalition against France and dispatched a combined fleet to reconquer the islands, their troops found in some of them a ready welcome. Corfu, with its French garrison, proved a tougher nut to crack. Only after several months’ siege and some fierce engagement did the French commander Chabot admit himself beaten. When Russian troops entered Corfu town in March 1799, they were enthusiastically greeted and the church bells pealed. The tactful Russian commander, Admiral Ushakov, proceeded immediately to St Spyridon’s church, there to give thanks for the victory.

For the next seven years, the seven islands enjoyed the status of an independent federal state – the Septinsular Republic – under the protection of Russia, but paying tribute to Constantinople. It was a curious and unnatural arrangement. […] By 1807 the Franco-Russian Treaty of Tilsit had restored the islands to French rule.

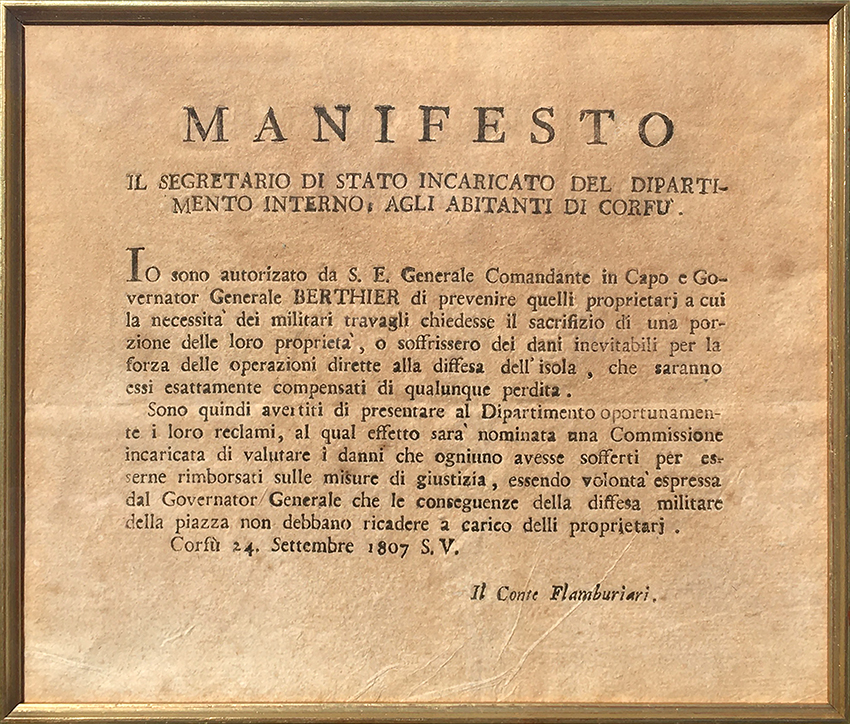

This second French occupation (1807-1814) was marked first by the wise and humane rule of Governor-General Donzelot (one of the main streets in Corfu town, bordering the harbour, is called after him), and second by the conquest of the southern Ionian Islands by the British and by their not very energetic blockade of Corfu. The executive powers were administered by the French Governor-General and the Senate, which in 1807 appointed a government limited to three ministers: Finance – Count Sordinas, Home Affairs – Count Flamburiari, Justice and Public Order – Count Karatzas. Donzelot remained firmly in control of the islands, and by these reforms and efficient administration made France as popular as before she had been unpopular. This time not only was St Spyridon not ridiculed, but his processions were carried out with proper respect and splendour. Newspapers were published, the Ionian Academy for the Encouragement of the Arts and Sciences founded, agriculture improved, and the whole system of government, still based upon mediaeval Venetian laws overhauled. Under the direction of Mathieu de Lesseps (father of the future creator of the Suez Canal), work began on building “Liston” on the north side of the Esplanade, the handsome houses rising above arcades, which recall the Rue de Rivoli in Paris.

Napoleon’s abdication in 1814 was followed by a tightening of the British blockade. Donzelot held out until the receipt of an order from the restored Louis XVIII to give way, and on 21 June 1814 Corfu came under the control of the British troops. […] Finally, in November 1815, a Treaty was signed in Paris under which the seven islands were defined as constituting “a single free and independent state under the exclusive protection of His Britannic Majesty”.

[Frank Giles, “History: The British Protectorate” in Corfu: The Garden Isle. London, UK: John Murray, 1994, pp 45-46]

This presentation is curated by Megakles Rogakos, MA MA PhD

PICTURES